Updated: Feb 23

March, 2021 – Patekka Bannister, Commissioner of Plant Operations at the City of Toledo, Ohio, and BlueConduit’s Ian Robinson spoke with CG/LA’s Norman F. Anderson. They discussed how the City of Toledo is Fighting Lead Lines with AI.

Highlight

We want to make sure that with BlueConduit’s help, we’re maximizing our resources. We are tax payer funded through our utility funds, through our rate payers. We want to make sure that we use AI and any other resources that we can find to help maximize those dollars and possibly be able to do this as quickly as possible. Patekka Bannister, Commissioner of Plant Operations at the City of Toledo, Ohio

Full Transcript

Norman F. Anderson:

Hi. Good morning. I just want to thank you all. Patekka and Ian, for joining us on GViP TV this morning. Thanks so much.

Patekka Bannister:

Thank you for having us.

Ian Robinson:

Thank you Norm. It’s great to be here.

Norman F. Anderson:

I know it’s really great to have you, let me start with a question for both of you, but let me direct it towards Patekka. Can you describe a little bit of your job Patekka? Love to hear, get a sense of what you do.

Patekka Bannister:

Sure. I am the Commissioner of Plant Operations for the City of Toledo Department of Public Utilities. That means I oversee the drinking water and the wastewater plants. But prior to that, I worked in our division of environmental services and oversaw water programs. So I have a deep passion for water quality and making sure that our customers are receiving an excellent product that we’re producing at our water treatment plant.

Norman F. Anderson:

That’s great to hear. One of my real interests in this whole business is water quality and understanding how we guarantee and provide levels of acceptable quality to people, not just in the US, but around the world. I mean, it’s a huge issue everywhere in the world. So thanks for the work you’re doing, super important. Ian, tell us a little bit about your business. You’re a different kind of duck in terms of what you’re doing. So tell us a little bit about your business.

Ian Robinson:

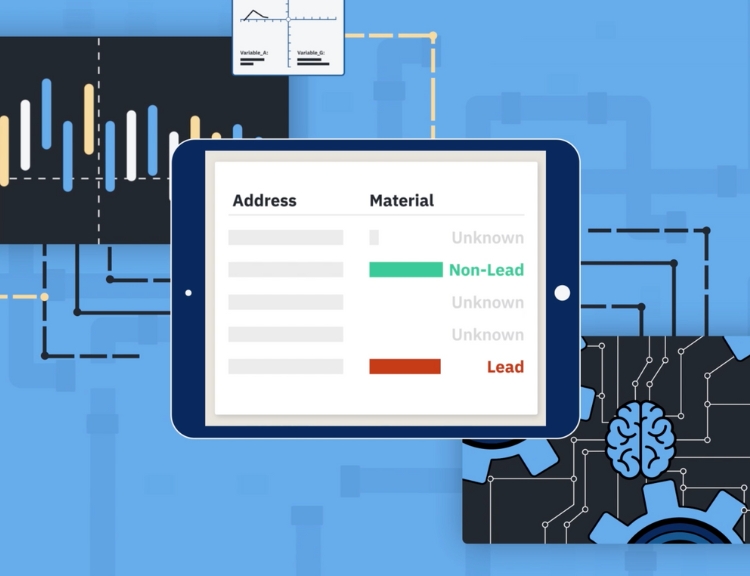

Thanks Norm. So at BlueConduit, what we do is we use machine learning methods to help cities reconcile and understand some of the uncertainties with their lead service lines and their service line inventories, essentially helping to best characterize where the lead service lines may be or may not be to inform decision making, helping get the lead out of the ground sooner, helping them make better decisions when it comes to how to integrate this data into decision making. We’ve seen a lot of issues about where the information is about these hazardous infrastructure risks and being able to help support cities and utilities and getting those out of the ground most efficiently.

Norman F. Anderson:

And is this a big problem in the US, in other countries as well? What’s your overall sense of the issue?

Ian Robinson:

So there are six to 10 million lead service lines remaining in the US. Lead has been banned as a material for service line construction since 1986. And just that range of uncertainty about how many service lines there are. It’s six to 10 it’s nearly, so that’s how many are there. And then how they’re distributed within cities is relatively either unknown. And there’s a lot of uncertainty. There aren’t a lot of good records about. In cities, we find them highly variable where either they exist or either they don’t exist or they’re outdated because a lot of these pipes, the service line is the pipe that connects the water main to the home were installed 70, 80 years ago. And there wasn’t a great record keeping back then or there’s been maintenance done since then. And what are the implications of this is that there is no other way right now to verify and check that there is lead service line material other than digging a hole.

Ian Robinson:

And so if you’re trying to replace pipes and you dig a hole, that’s thousands of dollars. If you find that pipe is copper instead of lead that’s money and time that could have been better allocated towards replacing a lead pipe. And if you had a sense of where the lead was, you’re able to concentrate your activities in those regions or in those homes, as opposed to ones with a high concentration of copper.

Norman F. Anderson:

Patekka, let me go back to you because you’re very interested in water quality and obviously lead is a huge issue, especially for young children. How do you see that? Is that a big problem in Toledo and other places around around Ohio and around the country?

Patekka Bannister:

Yes. Lead is an important issue around the country. Here in the city of Toledo, we started looking at really in the late nineties about our lead levels. We’ve had concentrated areas of testing that we’ve done. That’s when we started making sure that we line our water distribution system so that our residents wouldn’t be impacted and we do testing annually for that. But really our concern is we want to limit having to do that. We really want to get those Lead lines out of our system. We want to get those lead fixtures out of our residential homes. And we’re guessing, and with BlueConduit, Ian’s help will have a better idea, but we’re guessing we have about 3000 residential units and within their homes that have lead service. So we want to make sure that we provide whatever resources we can. And those tend to be concentrated in areas that have had equity issues within the neighborhoods.

Patekka Bannister:

So we’re very conscious of that. And we want to make sure that anyone that might not have that resource to remove those that we develop programming that we can assist those homeowners with removing those lines. And then on our end of it, we want to make sure that with BlueConduit’s help, we’re maximizing our resources. We are tax payer funded through our utility funds, through our rate payers. We want to make sure that we use AI and any other resources that we can find to help maximize those dollars and possibly be able to do this as quickly as possible. We’re we’re figuring right now, this was before we introduced BlueConduit into our program, but we were thinking it would take about really 30 years to be able to complete.

Norman F. Anderson:

Oh my!

Patekka Bannister:

So, anything we can do. And we share that with anyone, any ideas, any sources that other people have that we can bring that number down we are open to it.

Norman F. Anderson:

That’s great. And in terms of working with BlueConduit, do you see that there’s a pretty good demolition in terms of how long it’s going to take for you guys to address the issues.

Patekka Bannister:

Right now, we are expecting to see our modeling information to come out soon, but really that is what our goal is, is to work with BlueConduit and properly identify those areas that we should target. And we have an Environmental Justice Grant through US EPA, and we are partnering with BlueConduit, but we’re also partnering on our outreach and education with Freshwater Futures.

Norman F. Anderson:

That’s fantastic.

Patekka Bannister:

And we think this is a good partnership because it allows other parties to come in and it’s not just whatever the government says, I’m the government I’m here to help, but we have outside organizations, we are going to involve five. We’re going to work with five neighborhoods and we’re going to concentrate our efforts with Outreach, so the information that BlueConduit comes out with, it’s also going to be user friendly. We’re going to work on developing a better map. We do have a map that we have on our website, but we really liked some of the ideas that BlueConduit worked on with Flint that were a little bit easier for a resident that maybe doesn’t have an engineering degree or a science degree could easily identify what’s going on in their neighborhood and their community.

Norman F. Anderson:

That’s fantastic. You it’s super interesting. Ian, Patekka mentioned Flint. Tell us a little bit about your work with Flint, your work with Toledo and the benefits that you guys provide. Representative DeFazio just yesterday presented the new water bill. And it strikes me that there ought to be a national… Patekka, you mentioned equity. There ought to be a national drive to get rid of, to address this lead pipe issue, because it is an equity issue in downtown center cities all over the US. And when you’re talking about one of things that drives me crazy about the water business globally is that 6 million to 10 million.

Norman F. Anderson:

That’s how people think about it. When we think about non revenue water all over Latin America, for instance, everybody always says it’s about 50%, and then you go, okay, so, and what’s stolen versus what’s lost by leaky pipes. And they go, oh, it’s about 50%, which you know they’re just guessing, and those are the World Bank Figures. So it’d be interesting to get a sense. What was your experience like in Flint, in Toledo and how quickly can you speed up the process of getting rid of the lead problem in our water system?

Ian Robinson:

Absolutely. And that’s a great question. I think when you think about the benefits to that BlueConduit brings to cities is cities are operating in this tremendous unknown, and they have this either this mandate or the desire to locate and replace their lead service lines. But if you’re working with imperfect information, you’re working with old records, it’s really hard to strategize. And so this is what our team did in Flint. So this project, BlueConduit, really our company emerged out of research that was done by university of Michigan faculty in Flint, in 2016, when at the peak of the water crisis there. And they identified the replacement of the lead service lines as the main… This is how our effort to remediate, it’s going to cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

Ian Robinson:

But the question of how many lead service lines are there in Flint and which homes are have lead pipes and which ones don’t were largely unknown. And so that’s where Eric Schwartz and Jake Abernethy and their team use their statistical methods and AI to help develop these home by home probabilities, which allowed them, allowed the city to target homes with the greatest likelihood of lead for replacement. And then, so that’s the first well, how can this accelerate. It gets the lead out of the ground sooner. And the impact that this had is in each city is going to vary based on the concentration of lead, but getting a full picture is essential for budgeting. So when you have six to 10 million leaded service lines in the United States, how do you even budget? If you think if the range of budget is anywhere between 30 to 50 billion dollars, that’s a lot of money. So just being able to understand the scope of the problem, and then being able to target your efforts makes a huge difference because then you can be proactive.

Ian Robinson:

And I think that’s one of the really… When working with Toledo, one of the great benefits in this work is the city has been very proactive when it comes to, as Patekka was talking about many, the city’s been prioritizing reducing lead exposure for many years and putting in place policies and partnerships that allow to get the lead out of the ground, but also to reduce lead exposure in the meantime. And so I think that’s also one of the benefits where we talked about the map, but this project with Toledo is really exciting because it’s not just about the removing the lead pipes. It’s also describing this as a process, that’s several years long. So how to best inform and educate residents in the meantime about potential risks and steps that they can take in about protecting their health and their families.

Norman F. Anderson:

That’s really I think important and super interesting. Patekka, I wanted to ask you quickly, as Ian talks about the quality of water again, I mean, I think that’s obviously the critical issue in Toledo. How do you all do what he just said, in terms of helping people understand what their water quality is on a daily basis? I suppose in, especially the people who are in the danger zone that BlueConduit identifies.

Patekka Bannister:

Well, it’s no secret that in 2014 city of Toledo had a do not drink advisory due to harmful algal blooms in Western Lake Erie. And that really brought water quality issues to the forefront here and our area. And so we have really had an effort to do outreach in working in the communities and explaining water quality, what to look for. It’s really interesting one of the funders for BlueConduit as a partner for them is Rockefeller Foundation and connected us and we were able to have a conversation. And one of the things they brought up is, for them and talking to other funders said, you know what? One of the things that would help the educational system is for the nation to start focusing on lead and the removal of lead lines in our infrastructure.

Patekka Bannister:

So, that really, really struck us how important this is to our communities. As I had mentioned, we’ve really been monitoring this for well over a decade, but really our focus now is let’s get this out of the ground. Let’s get these out… Let’s get these pipes out of the homes. So we don’t have these issues to continue to be concerned about. And as I mentioned, we’re going to be working more hand hands on with the community so that they have an understanding of water quality and how important it is to their families.

Norman F. Anderson:

As I listen to both of you all, this is what we call lighting a candle in the darkness, right? Because, without the kind of analytics that BlueConduit does, it’s hard to get your mind around the problem. As Ian said, it’s hard to figure out how to address the problem. And it strikes me that probably the business, the work that you all are doing in Toledo, it’s probably needs to be done in how many municipalities Ian, around the US. And I agree with you all that this should be a priority. So I think what we’re going to do with this interview is see if we can get this directly into the hands of people all over the country. And I apologize for giving you guys more work, but then they’ll probably ask you how to do it, how to get started and how to address the issue. But it strikes me that this is the kind of thing that children don’t have a voice, people who are drinking bad water don’t really have a voice. Sounds like you guys are the voice for those people.

Ian Robinson:

I mean, that’s exactly why we were founded as a company, seeing what was happening in Flint and then hearing about it in when other companies selling utilities reached out and said, heard about the work that our team had done in Flint and said, can you do this elsewhere? And this is a nationwide issue. It’s a nationwide issue when it comes to infrastructure that it’s this way, but really Norman as you’re talking is, this is a public health. It’s the relationship between infrastructure in public health, the continued presence of these lead service lines and communities really, they don’t need to be there and they continue to pose a risk to the development and of children and of our communities and the way to make sure that the lead is not affecting their development, is to get it out of the ground and replace it.

Ian Robinson:

And that’s what we are committed to doing. And by using these data driven methods, we can save millions of dollars in doing it. But most importantly, the cost savings is one part of it, but really it’s the time savings. It’s the reducing the amount of time that residents are living with lead service lines connect, going into their home. And that’s what we’re really motivated to help communities get their hands on and then develop strategies to do that. Similar to what we’re doing in Toledo can be done anywhere else in the country.

Norman F. Anderson:

That’s phenomenal. Patekka, I’m going to give you the last word. I really appreciate you both of you taking the time, but give us a sense of how you see this program. Let’s say you’re in charge of… let’s say you’re at the EPA in Washington, and you’re going to roll out this program across the country. What would you do? Because you have more experience in addressing this issue than anybody. So it’d be really interesting to get a sense from somebody who’s addressing the issue locally of what we should do, how we should think about it nationally.

Patekka Bannister:

I had the opportunity to go through and look at some of the articles and the letters and the memos from when our plant was first constructed in the 1930s and early 1940s, and how the citizens there really wanted water quality. They knew that there was a tie to economics. There was a tie to public health. And I really think it’s time for us to focus and reinvest in our infrastructure and reconnect and refocus to our water systems. So I think that’s really something that we need to think about as a nation and how important this is. And as I mentioned, it’s tied to behavior and being able to focus for young kids. These are important issues to us as a country, and it’s time for us to make those investments.

Norman F. Anderson:

I really appreciate you guys, thanks so much for your work and your dedication, and also not just bringing this problem to the country’s attention, but to doing it. So articulately and creatively. So thank you so much for your time. It’s really a pleasure to meet you guys.

Patekka Bannister:

Thank you.

Ian Robinson:

Thank you.