Got questions about the Lead and Copper Rule Revisions (LCRR)? BlueConduit’s Sheela Lal gave us answers in a brief, to-the-point 30 minute webinar on May 25, 2022.

Sheela presented what is required of public water systems, by when, and how to get started. You will learn how to approach organizing the data needed to create your inventory of the public and private service lines.

Lunch & Learn Webinar Video

Lunch & Learn Webinar Transcript

Sheela Lal (00:02):

Okay. It is 1:00, and this is only a 30-minute webinar, so I’m going to go ahead and get started. First, I want to thank everybody for registering and actually attending. This is really a really big deal for us. This is our first 30-minute lunch and learn webinar. My name is Sheela Lal, and I’m responsible for our public sector relationships here at BlueConduit. And many if not all of you are experts in your field. Much of the information presented here is a compilation of facts and interpretations that the BlueConduit team has gleaned from you all. I want to mention this before I get started, because it’s critical for all of us to work together to share information, best practices, failings, and next steps to make sure that we can actually get lead service lines documented and out of the ground.

Sheela Lal (00:48):

So a quick agenda. My presentation will be brief. It’ll be between 10 and 15 minutes long. And then I want to keep time for any Q&A. As you can see on the screen, there should be a Q&A option at the bottom of yours, and please feel free to leave any and all questions there. If I’m unable to answer them in this time allotted, we will definitely follow up by email. So I saw that there was some anonymous attendees. If you just put your name next to your question, we can get that to you as well.

Sheela Lal (01:25):

So I want to jump back about 30 years to understand what the Lead and Copper Rule is and why it’s so important. So first issued in 1991, the Lead and Copper Rule is a US federal regulation that limits the concentration of lead and copper allowed in public drinking water at the consumer’s tap, as well as limiting the permissible amount of pipe corrosion occurring due to the water itself. The rule required a public water system serving more than 50,000 people to survey their corrosion control systems and obtain state approval for their systems by January 1st, 1997. Smaller systems were only required to replace their pipelines if action levels were exceeded in measurements taken at the tap, which sounds familiar in the context of the new Lead and Copper Rule revisions. I also want to note that in the mid 2000s, around 2004, 2005, the EPA did a study of the effectiveness of the Lead and Copper Rule and noted that the system had been effective in 96% of systems serving at least 3300 people.

Sheela Lal (02:30):

So all of this to say, the Lead and Copper Rule has been around for a long time. There have been longer grace periods to become compliant, but that at the end of the day it works, and it does keep all of our residents and water drinkers, which is everybody, safe from exceedances in lead and copper for the most part.

Sheela Lal (02:53):

So you’re here because you want to understand a little bit more about the new revisions that were approved in December of 2021. So the new Lead and Copper Rule better protects children and communities from the risks of lead exposures by better protecting children at schools and childcare facilities, getting the lead out of our drinking water, and empowering communities through information. So we’re taking just the compliance that the water system had to do and amping it up a notch.

Sheela Lal (03:21):

Improvements under the new rule include… And this is five parts. The first is using science-based testing protocols to find more sources of lead in drinking water. Very few water systems know where their lead or galvanized pipes are located, and many rely on historic data to guide their decisions, which is not always available or very reliable. The Lead and Copper Rule revisions now require public water systems to create an inventory of all service lines within their distribution system, including identifying lead service lines and galvanized, so that systems know the scope of the problem, can identify potentially sample solutions, and can communicate with households that are or may be served by lead service lines to inform them of the actions that they may take to reduce their risks.

Sheela Lal (04:10):

The second is establishing a trigger level to jumpstart mitigation earlier and in more communities. So I want to make it clear that there’s no safe level of lead in anyone’s water. So as an industry, as an entire water ecosystem, we should all be aiming for zero parts per billion. The EPA has established limits for the action level and trigger level which are not zero, but we are fully hopefully working towards that end goal.

Sheela Lal (04:38):

So a core component of the lead and copper goal is maintaining an action level of 15 parts per billion. Every time I hear this, personally, I’m curious, what does that mean in scale? So bear with me if you’re already familiar with this, but I think it helps put it in perspective. Parts per billion or one part per billion is the equivalent of one microgram per approximately one liter of water. One million micrograms is one gram. So one billion micrograms is a kilogram. And these are very small units but important to understand for this conversation.

Sheela Lal (05:11):

15 parts per billion serves as a trigger for certain actions by public water systems, such as lead service line replacement and public education. The Lead and Copper Rule revisions did not modify the existing lead action level but established a 10 parts per billion trigger level to require public water systems to initiate specific actions to decrease their lead levels and take proactive steps to remove lead from the distribution system.

Sheela Lal (05:39):

Number three, the Lead and Copper Rule revisions will empower or will ask all of us to drive more and complete lead service line replacements. So we recognize that with the word more, there’s limited funding for states with the highest estimated number of lead service lines. And for those systems to identify and remove those lines, accuracy and order are the keywords. And for a complete replacement, the LCRR does not allow any more partial replacements except in emergency repair.

Sheela Lal (06:12):

Number four, for the first time, the lead and copper role is now requiring testing in schools and childcare facilities. Number five is the Lead and Copper Rule is requiring water systems to identify and make public the locations of lead service lines. And I’m sure we’re all familiar, but just to reiterate, the compliance state for the final rule published on published on January 15th, 2021 is now October 16th, 2024, so that’s less than 17 months from now.

Sheela Lal (06:47):

And let me know if you can see my screen. Sorry, my computer just freaked out at a very inopportune moment. But what can BlueConduit do to help with these requirements? I do want to emphasize that I’m not trying to make a sales pitch. I’m just trying to do an educational webinar. So I’m not trying to like say you all have to use BlueConduit, but just recognize that there are a lot of options out there, and this is how we can help with the Lead and Copper Rule revisions. So we can help with two out of the five requirements, which is developing an inventory and helping with the replacement plan.

Sheela Lal (07:24):

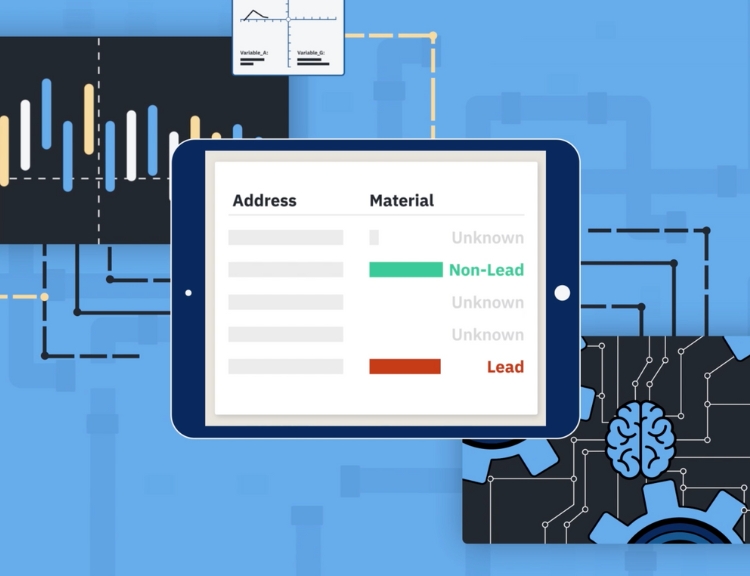

But I actually want to back up a little bit and… Sorry, one second. And talk about, what is predictive modeling? Predictive modeling is a mathematical process used to predict future events or outcomes by analyzing patterns in a given set of input data. It is a crucial component of predictive analytics, a type of data analytics which uses current and historical data to forecast activity, behavior and trends. So we see that this can be used in a lot of fields. We see it specifically in finance, in healthcare and in marketing. And so this isn’t a new type of statistical analysis or math or science that is being used to understand behavior.

Sheela Lal (08:09):

The model uses information… Our model, the BlueConduit model, uses information that is known to help make predictions about information that is not known with certainty. It combines existing service line data, historic and recently verified, and the results of inspections at a representative set of unknown service lines and other relevant parcel data to generate home-by-home probabilities of the presence of lead service lines. And gathering verified inspection data from a representative set of unknown service lines allows BlueConduit to reduce potential data biases and improve the model’s efficacy. These are both really, really important aspects to how we build our algorithm and practice in the field, because they’re the basics of good statistics. This practice is a key tenant for how BlueConduit approaches its work of predictive algorithms that promote equity and not just going for specific neighborhoods or the low-lying fruit.

Sheela Lal (09:09):

The relative predictiveness of different features describing a service line and a parcel varies from community to community, and we work to get as much data as we can about a city, train the model on representative data, and allow the algorithm’s feature selection to determine which features have the greatest predictive weight. If you could bear with me for one second, my computer is still not wanting to work, so hold on.

Sheela Lal (09:39):

Apologies for that. So I want to talk a little bit about what the Lead and Copper Rule improvements mean and what the EPA is saying about predictive modeling. So the EPA guidance to clarify how you do the Lead and Copper Rule revisions is called the LCRI, which is the Lead and Copper Rule Improvements. It’s anticipated, and we’ve been hearing that it is going to be released next month since March, so fingers crossed it’s actually released next month. In the meantime, we’ve received many questions about what methods will be accepted by the EPA. And I just want to say that the EPA currently uses predictive modeling tools in other programs, indicating their comfort with methodologically sound predictive modeling as a tool. So they use it for their assessing chemicals under the Toxic Substances Control Act. They use it for the Support Center for Regulatory Atmospheric Modeling air quality program. And they use it for their estimating programs interface for chemical properties and environmental properties to indicate where chemical will go into the environment and how long it will stay there. So the EPA is already doing this. We don’t see any reason why they would not take, again, high-quality statistical modeling for the Lead and Copper Rule.

Sheela Lal (11:08):

The EPA has also stated before that predictive models could also inform water systems in how they can approach lead service line replacement in a more efficient manner. The EPA encourages this practice, as it allows consumers with lead status unknown service lines to be informed sooner about their service line material. So again, the EPA has stated this in a public comment. They’re also not usually in the business of micromanaging. And we recognize that having used predictive modeling in other programs that all of this together might mean that they’re going to be completely fine with how we do predictive modeling for lead service line inventory.

Sheela Lal (11:53):

But regardless of method, let’s talk about the inventory itself. All inventories will be created with a mix of verified information and assumed information. The ratio between the two varies drastically by water system. There are some water systems that have been able to update their service line material data as they conduct other asset management projects, while many others are going to build their inventories with some to minimal historic records. The less verified information available to a water system, the more assumed risk they’re working with. Predictive modeling, especially done with strong statistical founded fundamentals, greatly reduces the risk in each of these assumptions. And that’s statistical assumption. I just want to be clear.

Sheela Lal (12:36):

So I’ll bring it back to the public health crisis that jump-started these rule changes, Flint. The City of Flint didn’t know how many lead pipes existed or how much federal money to ask for to get rid of said pipes. Their historic records indicated that 10 to 20% of the city lines were made of lead. A home inspection project revealed about 3% of the city had lead service lines. And then in the first 170 digs, 96% of those lines were lead. That’s a 93% range, and that’s impossible to plan with, and it’s also impossible to budget with. The founders of BlueConduit recommended that crews inspect 300 homes in a representative sample with a hydrovac. And from that, we’re able to use the algorithm to estimate that 37% of the entire water system would have lead lines. Five years and more than two 25,000 pipes later, we see that the actual proportion of active water accounts with lead service lines was 39%.

Sheela Lal (13:34):

So each water system has to decide how they want to create their inventory. Do they want to use current staff time to develop an inventory based on historical data? Do they want to use an inventory purely based on historic data to inform their water asset management programs for the next five years, and then update their inventories over time? Do they want to create an inventory that minimizes their false positives and false negative records? And do they want to spend more of their time on a replacement plan or in developing the inventory? Because remember, we only have a certain amount of time.

Dunrie Greiling (14:10):

Sheela, we can take the slides if….we’ll take over hosting.

Sheela Lal (14:16):

Yes, that’s completely fine. Sorry about this. Some technical difficulties.

Dunrie Greiling (14:21):

And then I will share, and you’ll just have to tell me when to advance.

Sheela Lal (14:27):

We are at the questions right now. I appreciate everyone’s patience with this technical issue. So we asked everyone who registered to pre-submit some questions, and I want to go over a few of them. I also just want to preface all of this with, you might think that I’m kicking the can down the road with some of these answers, but what I’m really trying to do is both encourage everybody on this call to talk to each other and recognize that we are not the EPA, and there are a lot of questions that we can’t answer because we’re not the EPA, and I don’t want to put false or poor information out into the ether. I’d much rather we recognize that these are important conversations to be had and that the folks with the regulatory power should be the ones answering them.

Sheela Lal (15:22):

So we have them broken up into some themes. The first one is implementation. So if a lead line is found today, are we required to provide them with a filter now, or only once we begin the replacement? And according to the wording that is available online, it is once you begin replacement.

Sheela Lal (15:41):

What is the best practice to verify private side lines? I did just talk about this in inventory. Obviously we have a little bit of a bias with using predictive modeling. But at the end of the day, it’s what type of data you have, how fast you want it to be done, and how you communicate that to your public.

Sheela Lal (16:05):

Are irrigation and fire lines supposed to be included in inventory? So I thought this was a really interesting question, which is why I kept it there. The water system lines connect varied water mains to… Sorry, let me back up. I actually had to understand what is a service line by definition in this industry, and that is one that connects varied water mains to buildings to supply potable water and sometimes to supply fire protection systems. So irrigation lines would not be included in this. And because the aim of the Lead and Copper Rule is to reduce and remove lead contamination in potable water, I think it’s fair to assume that fire lines are also excluded. But I would also recommend reaching out to your state primacy agency or the regional EPA for clarification.

Sheela Lal (16:53):

And then last on this slide, what is considered acceptable proof that a galvanized line was never upstream of lead? Galvanized downstream of lead is what is of concern. Verified installation records or verifiable codes and ordinances are examples of that provided proof. Since so many records were never captured or are unreliable, there’s no way to absolute guarantee a specific code was always followed, and you have to assume the upstream service line could have been lead.

Sheela Lal (17:41):

Could you go to the next slide? Thank you. So these questions are about accessing the private side. So the first question is, what are some tactics to assist utilities to legally work on private property to replace lead service lines? And the second is, will partial replacements be allowed anymore under the new rule, or only full replacements? What if customers refuse private service line identification or replacement? Do systems just document this as a refusal and move on?

Sheela Lal (18:13):

So to the first one, something that we’ve been hearing is that cities are working on passing ordinances to empower water systems to access the private side. I do think it’s very, very important before a city does this type of legal ordinance protection work that the water system or the city are working to proactively communicate what is happening to your residents and not scaring them when they show up and just using like the guise of an ordinance to protect them. At the end of the day, the entire point of these new regulations is also to empower two-way communication and making sure that residents feel comfortable with what’s happening in their water system.

Sheela Lal (19:02):

To the second question, I spoke on the first part. Partial replacements will not be allowed. But if a customer refuses access to the private side, there hasn’t been any guidance around this yet, but I think it makes sense that systems would just document it as a refusal and move on and try to come back, maybe try to communicate with them to move from refusal to verified information. You can go to the next slide.

Sheela Lal (19:41):

Okay. So this is kind of a messy… Yeah, kind of a messy infographic, but all of it to say that we got a really good question on… Sorry. This one? Hold on one second. Sorry. I lost my place. There was a question on… Never mind. We can just skip this slide, because I do not have the context for that, and that’s on me. I apologize for that.

Sheela Lal (20:15):

Yeah, this is great. I really love that there were so many people who asked about data. The questions were, are assumptions allowed? What is the best way to organize your data? And how to gather all/any existing data to input into the BlueConduit model, is what I assume they meant by the model. So I want to say the EPA and most primacy agencies have not published their reporting mechanism of choice, but this is an example of how we did our data organization in Flint. I also want to give a shout-out to the State of Kansas. They have published an Excel spreadsheet template for all water systems to use. I would recommend looking at that if you wanted any inspiration. Sorry. That being said, the State of Kansas is requiring a lot more than what many other states will require.

Sheela Lal (21:07):

In terms of gathering any existing data to put into the model, we have an easy to use upload page on our product, and I don’t want to turn it, again, into a pitch, and so we’ll pivot to the types of data we generally receive, which ranges from the very minimum, which is verified information, to the ceiling, which doesn’t exist, because we will take any and all data to triangulate and really make sure that we are providing the highest level predictions for the context of that water system.

Sheela Lal (21:39):

And then are assumptions allowed? I didn’t know if this question meant statistical assumptions or if it meant general assumptions. And so the question goes on to say, “For instance, if a neighborhood was built the same year, can we pothole one property and if it’s copper assume the entire neighborhood is copper?” We saw in Flint and we continue to see in the 50 plus other water systems that we’re in that you can’t make that assumption, because records have not been kept well, or people make those big changes without necessarily grabbing a permit.

Sheela Lal (22:18):

And I can talk a little bit about where I live. So I live in an older part of my town. My house is 90 plus years old, but there are two houses down the street for me which are brand new, and every other house is kind of in between. Our house has a lead service line. I’m making the assumption that the two houses down the street have copper. But I can’t make any sort of assertion about any of the other houses on my block. So assumptions, probably best to stay away from. We understand that age of home is a really strong indication, but at the same time, better to be safe than sorry.

Sheela Lal (22:55):

And we can go to the next slide. I think this is one of the last… This is the last. Perfect. We have seven minutes left for questions. My email is sheela@blueconduit.com. Please do not hesitate to reach out to me. And I will turn it over to Dunrie provide the questions, if anybody has asked questions.

Dunrie Greiling (23:18):

Please drop any questions into the Q&A widget. Sheela, there have been some other questions that came in that didn’t make it into the slides.

Sheela Lal (23:27):

Yes, and I am happy to answer those as well.

Dunrie Greiling (23:29):

But this is a great opportunity for those of you who are on the call to get your actual questions answered, so please drop them in. Maybe, Sheela, do you want to take a warmup from the list?

Sheela Lal (23:44):

Yes. So I’m just going to go in order. The next one on my list was, how do you collect private side inventory accurately? And will the Ohio EPA accept AI or predictive modeling as an acceptable solution? So a way to collect private side inventory accurately, there’s a lot of… I think, again, this goes back to your communications plan and how a water system chooses to engage with its residents. If it’s being proactive, explaining what the issue is and why they need their participation, I think that’s a really great way of building that trust and accurately getting that information over time. And I want to say with regards to the Ohio EPA that currently one of our predictive modeling projects is being funded by the H2Ohio grant, so it seems like they are accepting it and are okay with it.

Sheela Lal (24:36):

And so somebody else asked about the format that will be turned into the EPA. I want to say that the EPA will probably ask about the full line divided into private and public, the material on both sides, and how the water system knows that, at the very least. Like I said before, Kansas has proposed a detailed spreadsheet which should indicate what type of data primacy agencies can ask for. I want to note that Greg Baird put a comment in the chat, so please do read that as well.

Sheela Lal (25:10):

And then somebody asked about what will state regulatory agencies accept in terms of how the utilities identify the material out of the service lines. So states will take the EPA guidance as a minimum and might require more information, again, like Kansas, New Jersey, State of Michigan. At a minimum, they will want the format I just mentioned. And then to quickly pitch BlueConduit, we’ll be able to match the requirements at each state level and report that to your specific primacy agency. So we’re not doing a one-size-fits-all. We’re happy to adjust as the states come out with their requirements.

Sheela Lal (25:52):

Yes.

Dunrie Greiling (25:52):

Got one question in Q&A widget.

Sheela Lal (25:53):

Perfect.

Dunrie Greiling (25:54):

Daniel Quintanar asks, “How does BlueConduit identify unknowns?”

Sheela Lal (26:00):

Yeah, so that is… Daniel, thank you so much for that question. That is our algorithm. Our algorithm uses… We intake a bunch of data. Again, we have to have verified information as well for the model to work. And that creates predictions for each parcel level, for each parcel in your inventory. I am not a data scientist, so I can’t answer the statistical part of that, but I will refer you to the Association for State Drinking Water Administrators website. We co-wrote a paper with them on statistical practices. And Daniel, if you would like, I’m happy to also send some other statistics-based academic papers to you.

Sheela Lal (26:52):

And then you also asked, “What is your accuracy rate?” This is a really interesting question. Okay, so it’s several different points, and I’ll explain why. If you just had the pure predictions, we’re at 90%. But we recognize that in the field and the reality of private side or the reality of how cities change, it drops to about 80%. And I say that with people not allowing you to come to their homes, or the lots are vacant, and maybe stuff is stripped. So all of that to say, there’s the reality that brings it down a little bit, but we are at around 80% if not more on average across our projects.

Sheela Lal (27:38):

Anonymous123 asked, “I understand that if a customer refuses to replace private lead service lines, then the public water system documents that as refusal and moves on. But Drinking Water State Revolving Fund and BIL funding can only be used for full of replacement, unless the private side did their side first.” Thank you, Anonymous123. That is a much better way of wording how I responded. And this is why collective and collaborative communication is so super important.

Sheela Lal (28:09):

I did want to address a question from somebody in Kansas who said that the state is requiring us to capture goosenecks, solders and fittings on 37,000 service lines. It’s not practical to go door to door or pothole everyone. How are we supposed to capture this information?” So BlueConduit is actually able to take these different parts of the service line into our algorithm as variables and provide those predictions as well. And so we’re currently doing that for a few customers across the country.

Sheela Lal (28:41):

Daniel asked, “Do you have any clients in Arizona?” We have none that we can talk about publicly, but we are always happy to work, again, across the country. Our algorithm is able to both predict the presence of lead service line and predict by inverse the lack of lead service lines, and both are very valuable for the Lead and Copper Rule.

Sheela Lal (29:06):

Also, I would be remiss in our last minute if I didn’t reflect on one of the three webinars that were happening yesterday. But the one with EPIC featuring Mike from WaterPIO really stressed the importance of having a strong, proactive communications plan. And I want everyone on this webinar to think about what that means for your community, because it not just impacts how your community sees you, but it impacts all of the other aspects to the Lead and Copper Rule revisions or other water management work that you’re doing to be successful. So there were a lot of questions that came in about communications, and that just reinforces this.

Sheela Lal (29:47):

But we are at the half hour. And I really want to thank everyone for their time, their attention, and their really incredible questions. Please do not hesitate to reach out to us moving forward. And Daniel, I see you had one last question, and I will answer that in an email, because we’re at time. But thank you. Thank you so much, everybody, for your patience with my tech, enthusiasm in showing up. And we will also have this recording available moving forward on our website, and our marketing team will follow up with a lot more of our collateral. So thank you again, everybody, and have a great rest of your Wednesday.

About BlueConduit

BlueConduit originated the approach of using machine learning to predict lead pipes and have been doing it longer than anyone else.

Our team has been helping local officials and their engineering partners identify and remove lead service lines since 2016.

We’ve now created our software platform to streamline this process for our utility and engineering partners.